Posted on 4th November 2021

by Jess Howard

Clipping: A thought provoking article that looks at why horses behave the way they do, and what we can do to minimise stress, and maximise welfare.

Clipping is a task that is considered essential in modern horse care, despite the itchy, time and labour-intensive nature of it, to help provide comfort and ease mostly in winter months when horses are likely to sweat.

There is no formal qualification or training required prior to clipping a horse or owning clippers and blades, and similarly there are no formal guidelines to help decide what clip is most suitable for the type of horse someone may have. Horses have extremely efficient thermoregulatory systems, (climate dependant) and they also have extremely sensitive behavioural repsonses attributed through years of evolution to help finance survival, but this is not always considered by everyone needing (or wanting!) to clip their horse, which is a historically stress inducing event. These aspects of Equus open the door to a menagerie of questions surrounding welfare; whether that be to do with the ‘correct’ clip for that horse, the way it is managed during the clipping process, using modalities such as sedation or twitching, and the way clippers are used and maintained by the operator. How many people truly understand how to clip without pinching the skin or the importance of the type of oil, or the blade spring tension? And more importantly, how many people truly understand their horses stress response from an endocrinological perspective, and employ correct (as opposed to available or ‘known’) tools to manage it?

The requirement of turnout for competition has also vastly changed in recent times and there are more horses seen with full clips (head and legs removed) than there was 10 or 15 years ago. There is a question to be asked regarding whether this is more to do with ‘trend-setting’ or truly to do with genuine individual horse care. The FEI recently banned whisker trimming, and clippers being used at shows in order to minimise stress and allow horses to be allowed to exhibit natural behaviours using all of their senses to do so, in which whiskers play an unbelievably large role. Inner ear hair is also another controversial element of trimming and perhaps that should be brought forward for discussion too.

This article seeks to look at the aforementioned in a little more detail; explain some of the jargon that surrounds some of the beliefs and traditions surrounding clipping, and also aid in helping you as a horse owner, groom, trainer or rider, make an informed decision about the horses under your care.

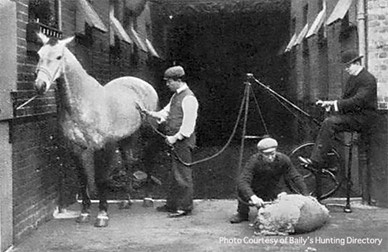

Clipping has been in practice for a long period of time, as far back as at least 1899, whereby the renowned ‘hunter clip’ was established, although using some unusual methods to complete the task. The first known clippers had a similar design to those we use today, but they had handles like scissors, and were man powered as opposed to electric or battery.

Gillette provided the blades for these contraptions, and Barton Gillette and Clarke’s provided staff and equipment to foxhunting clubs to clip the horses. Barton Gillette’s ‘Combination Clipping Machine’ (Fig.1) claimed to be able to clip ‘two animals in minutes’, with blades that could be used 80 times before requiring sharpening. This was all available at a hire price of £12.00, which roughly equates to around £1050 in modern monies. It is assumed that the cyclist would have had to be substantially fit to be able to meet this advertised standard!

Army regulations for World War One stated that all horses were to be clipped out by November, and is still a practice that is generally followed today in line with the clock change and reduction in daylight hours that occurs at the end of October. Clipping generally stops between the end of January and beginning of March time, whereby there is another clock change shortly after and daylight hours begin to draw out again, in preparation for spring and summer coats to come through.

As well as the well established ‘hunter clip’, other clip types were utilised generally based on discipline choice, and therefore workload expectation and living arrangements. Trace clips were used by carriage horses, with the clip lines following the line of shafts in a driving vehicle, while racehorses and steeplechasers generally had ‘chaser’ clips. Native breeds were not clipped as a rule, due to their requirement to work in extremely tough weather conditions on moors and highland areas, where they would be expected to work at a slower pace for a longer period.

Fig. 1. ‘Combination Clipping Machine’, Brook (2021)

The general reasoning behind clipping has been to prevent horses from catching a chill after working in winter months when they are likely to sweat more. However, it does need to be taken into consideration whether the horse in question lives in or out, how much rugging up it requires, its breed type, and most importantly its workload.

Horses that suffer with conditions such as Cushings may require clipping as part of their management, as will older horses or ponies whose bodies are less able to react to temperature change. Older Shetland ponies are especially susceptible to growing extremely thick undercoats and they become too hot, requiring a minimal clip to keep them comfortable such as a ‘bib and belly’.

Professional riders and trainers that have horses in work for competition tend to opt for the full clip which takes the head and legs off, but sometimes leaving a patch for the saddle to sit on, or the hunter clip, as described further up. This is widely considered to be smart turnout, and in most cases, necessary for the level of work the horse is carrying out. These clips are both suitable for a horse that is stabled, in full work, with only an hour or two of turnout per day, however some younger horses with differing living arrangements that do less may receive the same extensive clip as their older counterparts, and it must be considered that while it may look smart and presentable in the show ring, the welfare of the horse in question does need to be considered too.

Equestrians that ride for recreation vary, dependant on experience and understanding. There is an element of ‘trend-setting’ that is prevalent amongst less experienced horse people, and there are a lot of incidences where a full clip will be carried out for a horse or pony that is only in light or medium work ‘because it looks nice’. This is not necessary and can lead to problems with temperature control during work and potentially muscle damage in extreme circumstances (horse does not get warm enough during exercise, and therefore muscles are forced to work when cold, which can cause damage, sometimes irreparable). In some instances, these horses are also rugged incorrectly for their clip and living arrangements resulting in difficulty with weight management during winter months.

A blanket clip, chaser clip and trace clip are all suitable for horses in light to medium work, those that work hard but for much shorter periods of time, or those that work for longer but at a much slower pace. Variations in height are all at the clipper user’s discretion and is often altered to that horses individual requirement, but can be used to cleverly improve the appearance of the horses conformation.

Everyone has heard the terms ‘make sure the tension is right’ and ‘oil your blades’ when clipping, but there is often not much more information than that. The tension of the blades can hugely impact not only the quality of the clip, but also how hot the blades get, how sharp they stay and also how much wear and tear the clipper motor is put under. Blades that have too much tension cause the clipper motor to work much harder, which can increase the temperature of the clippers themselves and the blades to an uncomfortable and dangerous level. Tension is generally measured in most clippers so that it is tightened to maximum and turned backward 1 and a ¼ turns to achieve the correct tension. This may vary slightly between clipper manufacturers, and it is important to check this if necessary.

Oiling blades shouldn’t be a dark art, but it is often forgotten about. Blades should ideally be oiled every 5-10 minutes minimum, in order to keep them from overheating. Oil means less friction, and excess heat caused by friction can cause clipper rash and an unhappy horse. Friction also causes the blades to go blunt much quicker!

Good quality oil is best, and many clipper manufacturers sell their own to complement their clippers. Some people do opt for the use of WD-40 as it is a convenient alternative, however unbeknown to many it is an extremely thin spray and evaporates too quickly, meaning it does not prevent friction and heat build-up, and can also get into the mechanisms of the clippers, washing out the heavy grease which will eventually destroy them altogether. WD-40 encourages dirt and grease to stick to it instead of washing it off (which is one of the ideas behind oiling the blades regularly when clipping).

To help combat some of the points made above and help to educate those that are not fortunate enough to have been taught in industry or by horsey relatives or friends, clipping short courses and training is often available. Equine Colleges run short half day courses open to those willing to learn how to clip under the watchful eye of a professional. It may look easy when done correctly but it is not always as straightforward as it looks!

Aside from clipper care, there is also how to put clippers together properly, how to hold them, how to stand, what angle to have the clippers at against the skin, how to clip awkward areas such as bony protrusions and how to create straight lines, not to mention correct preparation of the horse beforehand such as bathing/hot clothing or grooming. Inexperienced clipper operators ideally should learn on a horse that is good to clip, not ticklish and allows the person learning to get a genuine feel. It is extremely easy to get it wrong, catch the horses’ skin by accident, bang the clippers against the horse, turn them on at the wrong time and spook the horse, or stand in the wrong spot. Getting a good smooth clip without tram lines from grease or missing bits of hair takes a great deal of practice and patience.

An inexperienced handler with an inexperienced or sensitive horse is a recipe for disaster, often resulting in horses that are then labelled ‘bad’ to clip with behaviour issues, and handlers that get frustrated and worried about the job in hand. This can then make what is already a stress inducing event for a horse much more upsetting, and other handlers in the future may risk injury as a result. Clipping training is inexpensive and often fun and sociable, and specifically designed for those that need a little guidance.

Many horses are labelled ‘naughty’ or ‘bad’ to clip. It is not often that time is taken to understand the mechanisms behind why, but many handlers are quick to find a solution to make the horse stop exhibiting the undesirable behaviour, mostly due to time constraints and for safety. Two examples of this are the use of a nose or lip twitch (an ear twitch should never be used under any circumstances) and sedation, whether that be oral or intravenous. It is thought that the use of a lip twitch produces an analgesic effect through the release of immunoreactive beta-endorphins, creating an effect similar to acupuncture (Lagerweij et al 1984). A study carried out by Flakoll et al (2017) found that in a study using 12 male horses, a lip twitch significantly decreased heart rate over a period of 5 minutes, however after this period it had an opposing response. Ear twitching was also tested and concluded an increase in heart rate and salivary cortisol levels, regardless of the length of application. Lip twitching was considered a short term but effective method of restraint, while ear twitching was considered to evoke a stressful response, immobilising horses through fear and/or pain.

Sedation is considered the expensive but failsafe and safest option, and often requires a vet for administration, unless the horse only requires a mild dosage from oral sedative. From a behavioural perspective, the horse cannot learn to accept clipping under sedation, as the bodies reactions are effectively slowed down too much to exhibit any usual behaviours, thus interrupting the learning process entirely. Horses under mild sedation are often more agitated for this reason – they are aware, but their body won’t move how they want it to in order to ‘survive’ this incident. Horses that require frequent clipping may be suited to embarking upon a training solution that aids to alter behaviour patterns in response to this stressful stimulus, as opposed to being consistently subjected to sedation (and frequent vet bills!).

In prey species such as the horse, outward behaviour changes from fear or distress may be masked as a means of survival, and therefore is not always a clear portrayal of underlying mental state (Berger et al 2003). Hall et al (2008) states that domestic horses also undergo some form of training to aid in increased acceptance of otherwise aversive procedures or situations, therefore a lack of response may not reflect the actual subjective experience of that animal.

Measurement of cortisol is currently an accepted indicator of stress, however blood sampling for cortisol analysis requires restraint of an animal, producing potentially confounding results, (Mormede et al 2007). Salivary cortisol levels are therefore used widely, and studies including that by Hughes & Creighton (2007) suggest that the time taken for salivary cortisol levels to increase post stressor are similar to that in blood plasma. In both cases the delay between stressor and hormone elevation only allows interpretation of the response to an overall situation as opposed to immediate response to a specific stimulus. With this in mind, another way of measuring this is sought.

Eddy et al (2001) suggests that changes in skin temperature are shown to have association with clinical and emotional responses in humans and other species, as the consequence of changes in peripheral blood flow due to vasoconstriction or dilation caused by activation of the sympathetic nervous system. Infrared Thermography is a non-invasive way of measuring the alteration in radiated heat related to this rapid change in blood flow due to the sympathetic activation and stimulation of the hypothalamic pituitary-adrenocortical axis, associated to the stress response. These two methods of measurement used in conjunction have been used extensively to help portray a truer picture of the emotional state of a horse in an aversive situation such as clipping, to improve welfare and horse husbandry practice.

Ten horses were presented either as Compliant (C) or non-compliant (NC) and subjected to a sham clipping procedure (with the blades removed) for a ten-minute period. Heart rate, salivary cortisol and eye temperature were monitored throughout. NC horses were found to be significantly agitated than C horses throughout the trial, with a significantly higher heart rate after the clipping procedure. Interestingly ALL horses showed an increase between 5 and 10 minutes into the procedure. This was accompanied by a significant increase in salivary cortisol concentration in ALL horses post procedure, with levels peaking at 20 minutes post clipping. Eye temperature increased significantly in ALL horses during the clipping, peaking at 10 minutes, with a rapid decrease after the clipping stopped (Yarnell et al 2013). Although there was not a significant difference shown between the groups eye temperature, the NC group did have a greater decrease in eye temperature post clipping. Despite the behavioural responses of C and NC showing large differences, the physiological responses suggest that ALL horses found the procedure aversive.

In 2020 at the FEI General Assembly, a new rule was passed as part of the veterinary regulations that the clipping or shaving of sensory hairs on the horse was to be prohibited. The Veterinary Committee stated that the horses’ sensory hairs must not be trimmed or removed as it reduces sensory ability in the horse.

The rule states that horses are not permitted to compete in FEI events ‘if the horse’s sensory hairs have been removed, unless individual sensory hairs have been removed by a veterinarian to prevent pain or discomfort for the horse’. It was added that ear hairs are not considered sensory, and that there is no perceived problem of sensory hairs around the eyes being trapped in blinkers of driving horses. Disqualification is the sanction that follows this rule, and is supported by other countries such as France, Germany and Switzerland where both whisker and ear hair trimming is banned to some degree and in some cases even written into animal welfare law.

While the whisker itself has no nerves, the follicle it grows from is extensively innervated. The signals from the whisker travel to a very specific region of the brain for interpretation and are so sensitive to vibration and changes in air current that they can inform the horses instantly about his environment. Harrison (2019) states this can be to avoid injury by detecting nearby objects, differentiating between textures, judging wind direction, and identifying food; including those that may be harmful or toxic. The horse has a blind spot beneath the muzzle and therefore whiskers are vital to their vision – without them they are effectively handicapped.

As well as Global welfare changes, clipper manufacturers have sought to design clippers that are battery powered, cordless and as quiet as possible to enable horses that do display adverse reactions to clipping to be catered for as best as possible, without compromising on quality of the clip. Battery operated clippers are generally slower in speed, so the blades may require sharpening more often so that they do not trap or pinch hair when they are beginning to go blunt. A bad experience in an already fraught circumstance can wreak havoc on the horses cognitive learning processes.

The learning processes of horses can be covered in another article altogether, but is extremely relative to clipping, and the experiences that the horse in question is given in the early days.

There are so many factors to consider when clipping horses that don’t just include ‘getting the job done’. Horses react in a variety of ways dependant heavily on their temperament, learning experiences and interpretation of instinct too. Owners, trainers and grooms alike should seek to make the experience as stress -free as possible, by carefully considering the type of clip required for that individual horse, the behaviour it is likely to display outwardly with respect to safety especially, and also the competency of the person handling the clippers. The combination of these factors do really make the potential difference between the creation of a beautifully clipped happy athlete, and a horse that is sore, scared and confused. Part Art, part Science. Choose wisely and consider carefully!

References

Armishaw, C. FEI bans Horse Whisker trimming as of July 2021 <https://www.eurodressage.com/2020/11/25/fei-bans-horse-whisker-trimming-1-july-2021>

Brook, P. (2021) Bailys Hunting Directory

Burke, R. What type of clip is best for your horse this winter? <https://www.irishsporthorsemagazine.com/which-type-of-clip-is-best-for-your-horse/>

Berger, A. Scheibe, K.M. Michaelis, S. Streich, W.J. (2003) Evaluation of living conditions of free ranging animals by automated chronobiological analysis of behaviour. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 35 pp.458-456

Eddy, A.L. Van Hoogmoed, L.M. Snyder, J.R. (2001) The role of thermography in the management of equine lameness. Veterinary Journal 162 pp.172-181

Flakoll, B. Ali, A.B. Saab, C.Y. (2017) Twitching in veterinary procedures: How does this technique subdue horses? Journal of Veterinary Behaviour. 18, pp. 23-28

Hall, C. Goodwin, D. Heleski, C. Randle, H. Waran, N. (2008) Is there evidence of learned helplessness in horses? Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 11 pp.249-266

Harrison, J. (2019) France bans trimming of whiskers.

Hughes, t. Creighton, E. (2007) Measuring cortisol as an indicator of stress response in domestic horses. Journal of Equine Studies 4 pp26-28

Mormede, P. Andanson, S. Auperin, B. Beerda, B. Guemene, D. Malmkvi, J. (2007) Exploration of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function as a tool to evaluate animal welfare. Physiol Behav 92 pp.317-339

Shearease (2021) Looking After Your clipper blades. < https://www.sheareaseltd.com/how-to-look-after-clipper-blades/>

Yarnell, K. Hall, C. Billet, E. (2013) An assessment of the aversive nature of an animal management procedure (clipping) using behavioural and physiological measures. Physiology & Behaviour 118 pp. 32-39

Subscribe today for all the latest Equine Advertiser news and offers direct to your inbox